Fermentation, a vital biochemical process driven by microorganisms, is widely applied in food production, energy generation, and agriculture. In 2026, fermentation is typically classified by its primary end products or industrial technical methods. Based on biochemical pathways, there are four main types of fermentation: lactic acid fermentation, alcoholic (ethanol) fermentation, acetic acid fermentation, and butyric acid/alkali fermentation. Beyond these well-known categories, fermentation also plays a foundational role in organic fertilizer production, converting organic wastes into nutrient-rich, plant-friendly fertilizers through microbial decomposition. Understanding these fermentation types and their agricultural applications is key to leveraging microbial activity for sustainable production.

Lactic acid fermentation is dominated by lactic acid bacteria, such as Lactobacillus, which convert sugars like glucose or lactose into lactic acid. This process is anaerobic, meaning it occurs without oxygen, and the resulting lactic acid lowers the environment’s pH, inhibiting harmful microbes—making it ideal for food preservation. Its most common applications include the production of dairy products like yogurt and cheese, as well as fermented vegetables such as sauerkraut, kimchi, and pickles. In the human body, lactic acid fermentation also takes place in muscle cells during intense exercise when oxygen supply is insufficient, producing lactate that causes muscle fatigue. While less directly used in organic fertilizer production, lactic acid bacteria are occasionally added as probiotics to improve soil microbial balance, indirectly enhancing fertilizer efficiency.

Alcoholic (ethanol) fermentation is primarily carried out by yeasts, especially Saccharomyces cerevisiae, or certain bacteria. These microbes break down sugars into ethanol and carbon dioxide (CO₂) in anaerobic conditions. This process is the backbone of the alcoholic beverage industry, used to make beer, wine, and spirits. In baking, the CO₂ produced causes dough to rise, creating the light texture of bread. In organic fertilizer production, alcoholic fermentation can occur during the initial decomposition of carbohydrate-rich organic wastes, such as crop straw or grain residues. However, it is often a transitional stage, as subsequent microbial communities convert ethanol and other intermediates into more stable organic compounds that serve as plant nutrients.

Unlike the previous two anaerobic processes, acetic acid fermentation is aerobic, requiring oxygen. It involves Acetobacter bacteria oxidizing ethanol into acetic acid, the main component of vinegar. This process remains critical in 2026 for food preservation and the production of fermented beverages like kombucha. In organic fertilizer production, acetic acid fermentation can occur in well-aerated compost piles or fermentation systems. The acetic acid produced helps decompose complex organic matter, such as lignin in plant residues, and adjusts the pH of the fermentation matrix, creating a favorable environment for other beneficial microbes involved in nutrient transformation. Additionally, the acidic environment can suppress pathogenic bacteria in organic wastes, improving the safety of the final organic fertilizer.

The fourth main type is context-dependent, categorized as either butyric acid fermentation or alkali fermentation. Butyric acid fermentation is performed by Clostridium bacteria, which convert sugars into butyric acid under anaerobic conditions. It is used in the production of specific cheeses and as a precursor for biofuels. Alkali fermentation, common in Asian condiments, involves the breakdown of proteins and fats into ammonia and alkaline compounds, such as in the production of natto or fermented fish. In organic fertilizer production, this category aligns with the decomposition of protein-rich organic materials, such as animal manure or food waste. Microbes like Clostridium and proteolytic bacteria break down proteins into amino acids, ammonia, and other alkaline compounds, which are then further converted into stable nitrogen-containing nutrients essential for plant growth. This process is particularly important in the fermentation of animal-derived organic wastes, transforming potentially odorous and harmful substances into safe, nutrient-dense fertilizer.

It is worth noting that in industrial manufacturing contexts, such as biofertilizer production, fermentation is also classified by physical state: submerged fermentation (SmF), where microbes grow in liquid nutrient broth, and solid-state fermentation (SSF), where microbes grow on moist solid substrates with little to no free water. SSF is particularly widely used in organic fertilizer production, utilizing solid organic wastes like crop straw, manure, and agricultural by-products as substrates. This method is cost-effective and efficient, as it directly converts bulky organic wastes into granular or powdered fertilizers, realizing resource recycling. In 2026, the application of SSF in organic fertilizer production is increasingly optimized, with locally available biomass resources being used to cultivate beneficial microbes, reducing production costs and supporting a circular bioeconomy.

In summary, the four main types of fermentation based on biochemical pathways each have unique microbial drivers, end products, and applications. Beyond food and beverage production, these fermentation processes are integral to organic fertilizer production, enabling the transformation of organic wastes into valuable agricultural inputs. By harnessing microbial activity through fermentation, the organic fertilizer industry not only addresses waste management challenges but also promotes sustainable agriculture by reducing reliance on chemical fertilizers.

Scaling Fermentation: Industrial Composting and Granulation Systems

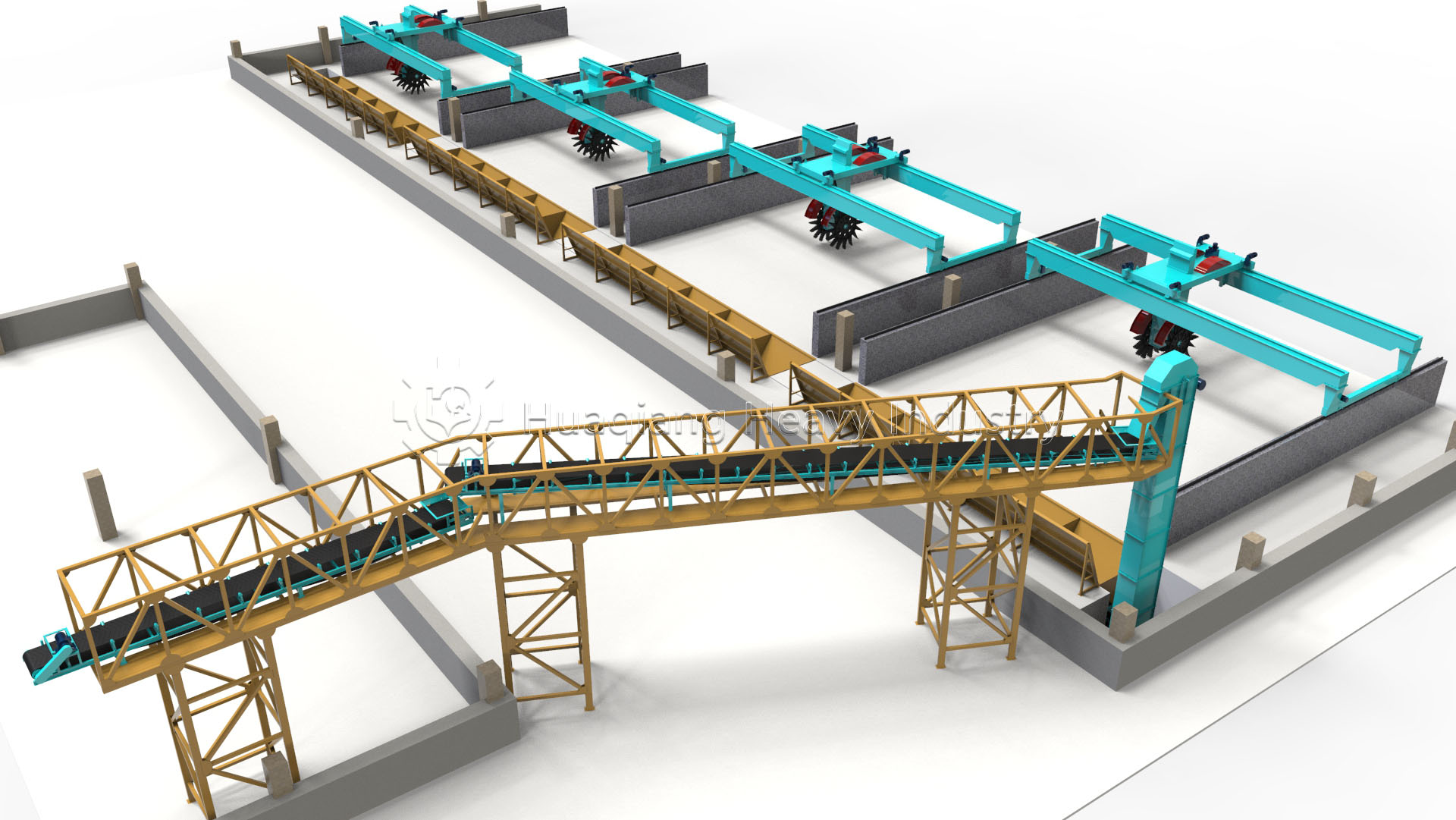

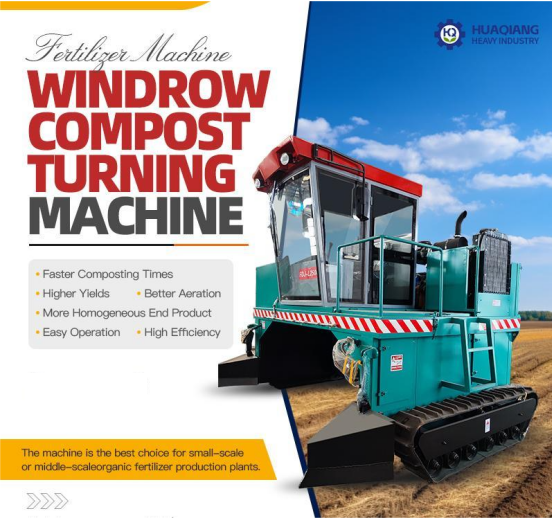

To industrialize the organic fertilizer fermentation process and manage the complex interplay of microbial activities, specialized mechanical systems are essential. Advanced fermentation composting technology for organic fertilizer relies on equipment that ensures consistent aeration, temperature control, and homogenization. In windrow systems, a windrow composting machine or a robust chain compost turner moves along elongated piles, providing the necessary turning. For more controlled, high-intensity processing, trough-type aerobic fermentation composting technology is employed, where a trough-type compost turner or a high-capacity large wheel compost turner operates within a concrete channel, optimizing oxygen supply and accelerating decomposition. This entire mechanical framework is the cornerstone of modern fermentation composting turning technology.

Following successful fermentation, the cured compost enters the next phase of the equipments required for biofertilizer production. This includes a multiple silos single weigh static batching system for precisely blending the compost with other powdered amendments. The blended material is then shaped using fertilizer granulation technology, often via a disc granulation production line, to create uniform, market-ready pellets. The integration of efficient turning machinery—from a simple chain compost turning machine to sophisticated trough systems—with downstream processing equipment creates a seamless, scalable production chain that transforms raw organic waste into a stable, high-value agricultural input.

Thus, the biochemical principles of fermentation are physically enabled and scaled by these specialized machines. The choice of composting technology directly influences the efficiency of the microbial process, the quality of the organic base, and ultimately the performance of the final granulated biofertilizer, closing the loop in sustainable nutrient management.