Mastering Variables: Crafting Better Slow-Release Urea Granules

Introduction: How is Good Fertilizer “Forged”?

In the field, we want nitrogen fertilizer to release slowly, nourishing crops persistently, rather than leaching or volatilizing quickly. Slow-release urea fertilizers are designed for this purpose. However, manufacturing high-quality slow-release urea granules is not a simple matter of mixing and pressing. It is more akin to a precise “culinary” process, where the raw material formulation is the recipe, and the granulation process is the heat and timing. A recent study delves into how adjusting two key “switches” in a disc granulator—binder concentration and granulation time—can precisely control the final “physical fitness” of fertilizer granules, thereby providing a scientific guide for producing more efficient and environmentally friendly slow-release urea.

I. The Core of the Study: Two Variables, Four Qualities

Imagine a rotating shallow pan where urea powder and a binder solution extracted from cassava starch are mixed and tumbled. The research team set up a clear comparative experiment: they fixed all other conditions like disc speed and inclination, and systematically changed only two factors: the concentration of the starch binder solution and the time the material spends tumbling in the pan for granulation.

They focused on these four “fitness” indicators that determine fertilizer quality:

1. Durability: Are the granules “tough” enough? Can they withstand collisions and friction during long-distance transport without turning into powder?

2. Density: Are the granules “fluffy” or “solid”? This affects the actual weight per bag of fertilizer, transportation costs, and application uniformity in the field.

3. Pelletizing Yield: How much raw material successfully turns into qualified granules? This directly impacts production efficiency and cost.

4. Water Absorption and Dispersion Time: Do the granules disintegrate quickly or release slowly upon contact with water? This is the core measure of their “slow-release” capability. We want them to dissolve like a slow-release candy, providing nutrients steadily in the soil.

II. Finding One: Binder Concentration—The “Glue” Matters

Cassava starch plays the role of “natural glue” here. The study found that the thickness of this “glue” has a decisive impact on granule quality.

When researchers increased the concentration of the starch solution, a positive chain reaction occurred: the granules’ water absorption, density, pelletizing yield, and durability all improved simultaneously. This is because a thicker starch solution forms a stronger, denser binding network around each urea particle. Just like using thicker glue for bonding, the adhesion is firmer, the structure is more compact, and the granules naturally become tougher, heavier, and have fewer internal pores.

More interestingly, granules made with higher concentration starch also “held on” longer in water. They disintegrated and released nutrients more slowly, which is the dream characteristic of slow-release fertilizers. Observations under an electron microscope showed that granules from the high-concentration group had surfaces like smooth, dense pebbles, while those from the low-concentration group had rough, porous surfaces, visually explaining the source of the performance difference.

III. Finding Two: Time—The Art of “Kneading”

Granulation time is like the kneading time when making dough. The study showed that extending the “kneading” time of the granules in the disc also led to comprehensive quality improvements.

Longer granulation time gives the powder more opportunities to collide, adhere, and round off. This results in more regular granule shapes and a more compact interior. Consequently, granule durability, density, and pelletizing yield all increased with time. Simultaneously, sufficient kneading allows the starch “glue” to distribute more evenly, forming a more complete coating. This not only slightly increases the granules’ water absorption capacity but, more importantly, extends their dispersion time in water, further optimizing the slow-release effect.

IV. Insights for Producers: How to “Customize on Demand”

This study turns complex processes into clear multiple-choice questions:

• If you want to produce high-end fertilizers with optimal controlled-release performance and superior storage/transport durability, the answer is: use a higher concentration of cassava starch binder and allow for a longer granulation time.

• If you need to strike a balance between production efficiency and cost to produce the most cost-effective product, you can utilize the data models derived from research to calculate the optimal combination of binder concentration and granulation time based on your specific requirements for granule density, strength, and release period.

It’s like mastering a precise “cooking” formula, allowing fertilizer producers to flexibly “customize” slow-release urea products with different specifications and performance according to market demand.

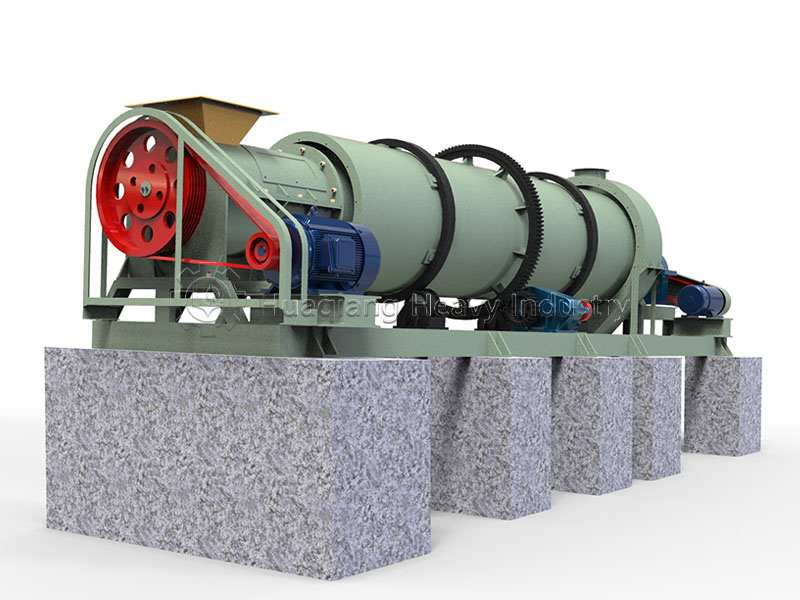

Optimizing Granulation: The Science Behind Consistent Fertilizer Pellets

The scientific study of binder concentration and granulation time directly applies to the core of npk fertilizer production technology. In a complete npk fertilizer production line, precise formulation using a npk blending machine ensures accurate nutrient ratios. The subsequent granulation stage, which is central to the npk fertilizer manufacturing process, leverages advanced npk granulation machine technology to transform this mix. The principles of optimizing binder properties and process timing are critical for equipment like a npk fertilizer granulator machine, whether it operates as a wet granulator or an alternative system like a fertilizer roller press machine for dry compaction.

Mastering these variables allows manufacturers to fine-tune the NPK compound fertilizer production capacity and the final product’s physical properties—such as density, strength, and dissolution rate. This level of control is essential for producing high-quality slow-release or controlled-release fertilizers. The integration of this scientific understanding into the operation of npk fertilizer granulator machine equipment demonstrates how empirical research translates into practical, scalable manufacturing excellence. It enables the production of consistent, “tailor-made” fertilizers that meet specific agronomic needs, enhancing nutrient use efficiency and supporting sustainable agricultural practices through precision engineering.

Conclusion

The power of science lies in transforming experience into quantifiable, replicable laws. This study on disc granulation process, through rigorous experimentation, reveals how two ordinary operational parameters—binder concentration and granulation time—act like levers to influence the final quality of slow-release urea granules. It not only provides a direct “operating manual” for fertilizer plants to optimize production but also brings us a step closer to the goal of producing more efficient, environmentally friendly, and intelligent “ideal fertilizers.” In the future, by exploring more “variables,” we can hope to design bespoke fertilizers, like precision instruments, perfectly tailored to the needs of every crop and every plot of soil.

.jpg)